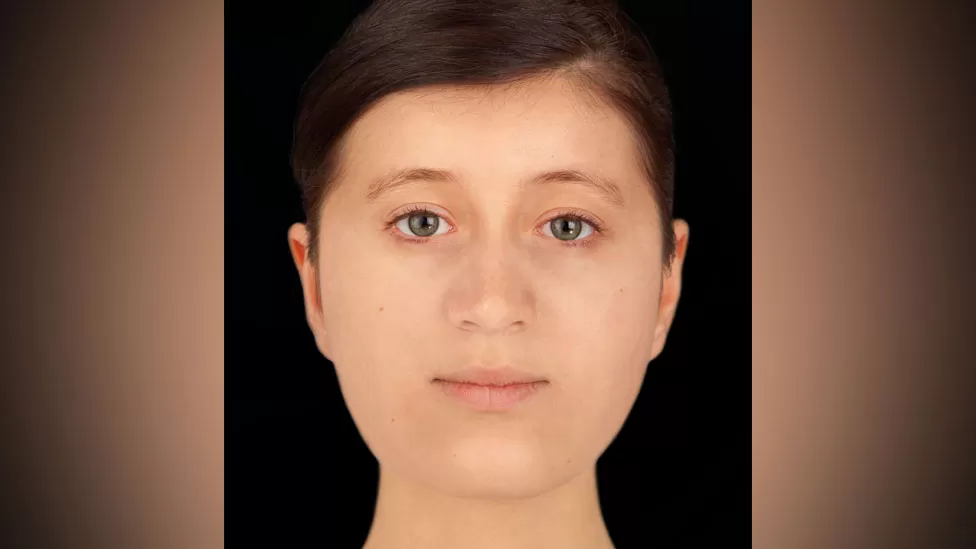

THE face of a girl who died more than 1,300 years ago has been revealed through facial reconstruction.

Her skeleton was found buried on a wooden bed, with a gold and garnet cross on her chest at Trumpington, Cambridgeshire, in 2012.

The image will go on display as part of a Cambridge University exhibition.

Anglo-Saxon specialist Dr Sam Lucy said “as an archaeologist I’m used to faceless people” so it was “really lovely” to see how she may have looked.

Forensic artist Hew Morrison created the likeness using measurements of the young woman’s skull and tissue depth data for Caucasian females.

“Her left eye was slightly lower, about half a centimetre, than her right eye – this would have been quite noticeable in life,” he said.

New specialist analysis of the 7th Century teenager’s bones and teeth has revealed more about her short life.

She was born near the Alps, probably in southern Germany, and moved to the flat, Cambridgeshire fens at some point after she turned seven.

In addition, her diet changed once she came to England.

Dr Lucy said: “We now know the proportion of protein dropped, suggesting she was eating more meat and dairy products when in southern Germany than on arrival in Trumpington.”

Cambridge University studies published last year revealed Anglo-Saxon kings were mostly vegetarian before the Vikings settled.

Researchers already knew from previous analysis that she had been suffering from an unknown illness before her death.

Dr Sam Leggett, who helped conduct the Cambridge University isotopic analysis before she moved to Edinburgh University, said: “She was probably quite unwell, she travelled a long way to somewhere completely unfamiliar – even the food was different – it must have been scary.”

The burial is one of only 18 bed burials uncovered so far in the UK, while the gold and garnet cross indicates her Christianity – and her aristocratic or royal background.

Dr Lucy said research into European bed burials “really does seem to suggest the movement of a small group of young elite women from a mountainous area in continental Europe to the Cambridge region in the third quarter of the seventh century”.

The woman could have arrived as a bride, or to join a monastic house like nearby Ely Abbey, and therefore she was part of “pan-European networks of elite women who were heavily involved in the early church”.

Dr Lucy said: “She’s a wonderful example of bringing the past to life.”