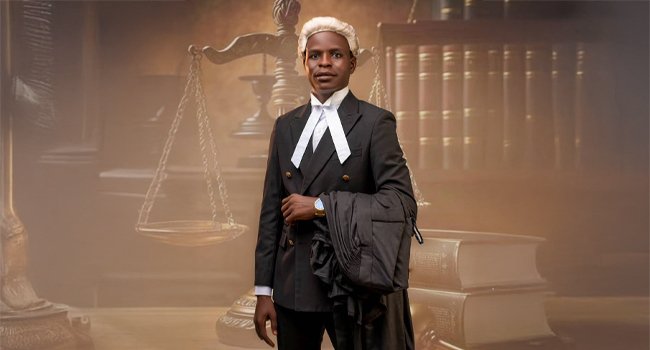

FOR Saminu Wakili, life has been a test of resilience, survival, and purpose. His bright smile and crisp black-and-white barrister’s robes may reflect the image of a promising young lawyer, but behind his formal legal attire lies the haunting past of a boy who fled Boko Haram violence with nothing but a will to live.

Born and raised in Gwoza, a community in Borno State, Wakili’s life was violently upended in 2013 when insurgents from the Boko Haram sect attacked his town, destroying homes, schools, and lives.

“They burnt our houses, burnt everything we owned,” Wakili recalled in a heartfelt interview on Channels Television’s The Morning Brief on Friday monitored by News Point Nigeria.

“We lost everything. We had no hope.”

Along with his parents and many other residents of Gwoza, Wakili fled across the border to Cameroon, one of several countries that received tens of thousands of Nigerian refugees during the height of the Boko Haram insurgency.

He spent his teenage years as a school dropout and refugee, struggling to survive from one camp to another. His only thought, he said, was not to die.

“We were displaced. We had nothing. I wasn’t even thinking of going to school, let alone becoming a graduate,” he said.

At that time, Wakili had no dreams of university, no hope of a career in law, and certainly no idea that he would one day be called to the Nigerian Bar.

In a twist of fate, a Good Samaritan named Pastor Solomon Folorunsho took interest in Wakili’s plight. On January 2, 2015, he helped bring the young refugee back into Nigeria, this time, to Benin City, where Wakili would join an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp run by Home for the Needy, a humanitarian mission supported by the International Christian Centre.

“In Benin, I resumed my secondary education. I had nothing, but we had peace, unlike back home where gunshots rang out daily.”

With the encouragement of the camp’s coordinator and support staff, Wakili worked tirelessly. He excelled academically, driven by a deep desire to prove that his circumstances did not define his destiny.

Wakili gained admission to Edo State University, Iyamho, where he studied law and eventually graduated with first-class honours, boasting a cumulative grade point average (CGPA) of 4.43, the best in his class.

Still separated from his parents, who remained in Cameroon and have not seen him in over 10 years, Wakili pressed on. In 2024, he enrolled at the Nigerian Law School in Enugu, successfully completed his training, and was formally called to the bar in Abuja on Wednesday.

“I haven’t seen my parents since 2015. I left them behind in Cameroon,” he said, choking with emotion.

“But I know they would be proud.”

Wakili’s journey is remarkable, but he is not alone. He is one of five IDPs from Borno State who were inducted into the legal profession this week. The others are David Ayuba, Nathan Ibrahim, Rifkatu Ali, and Peter Mazhekwatte Isaac—all residents of the same Home for the Needy IDP camp in Edo State.

Together, they represent a powerful symbol of hope, resilience, and what can happen when displaced persons are given opportunities, education, and care.

The Boko Haram insurgency, which began in 2009 as a radical opposition to Western education and secular governance, has killed over 30,000 people and displaced more than two million, mostly in Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states.

In 2014, then-President Goodluck Jonathan called on the international community to help Nigeria identify and prosecute sponsors of the group, warning that “peace and development are two sides of the same coin.”

Today, survivors like Wakili serve as a testament to the toll of the conflict—and the possibility of recovery.

Now a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, Wakili says his goal is not only to practice law but to become a voice for the voiceless, especially those displaced by conflict like himself.

“This is what the IDP camp did for us. This is what men can do when they refuse to give up,” he said.

Wakili’s story is more than just a personal success; it is a national parable—one that illustrates the power of hope, support, and determination in the face of unimaginable hardship.

In a nation where millions still languish in displacement, Wakili’s journey reminds us that with the right interventions, a refugee child can become a lawyer, a leader, and a symbol of Nigeria’s untapped human capital.

“I came from nothing, from being a refugee. Now I am a lawyer,” he said, smiling again—but this time, we know the weight that smile carries.