THE Trump administration is treating South Africa almost like a pariah, blacklisting its envoys, refusing to send top-level officials to meetings it hosts, and threatening to hit the nation with such high tariffs that its economic crisis is likely to deepen.

The latest sign of this came with the revelation by the second-biggest party in South Africa’s coalition government, the Democratic Alliance (DA), that the US government had rejected President Cyril Ramaphosa’s special envoy, denying him a diplomatic visa in May and refusing to recognise him as an “official interlocutor”.

Ramaphosa had created the post for Mcebisi Jonas, the non-executive chairman of mobile phone giant MTN and a respected former deputy finance minister, to improve South Africa’s rock-bottom relationship with the US.

Ramaphosa’s spokesman accused the DA of “disinformation”, but did not explicitly deny the party’s claim. The US State Department declined to comment when contacted by the BBC, citing “visa record confidentiality”.

Jonas’s appointment came after President Donald Trump had cut off aid to South Africa, accused Ramaphosa’s government of persecuting white people, condemned it for binging a genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and for “reinvigorating” relations with Iran – an implacable foe of the US.

Priyal Singh, a South Africa foreign policy expert at the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies think-tank, told the BBC that if the DA’s claims about Jonas were true, it would be in line with the Trump administration’s strategy to give South Africa the “cold shoulder, and cut off channels of communication that it so desperately needs”.

The US has not only cut back bilateral relations with South Africa, but also boycotted it in global bodies like the G20 – which Ramaphosa currently chairs, hoping to advance the interests of developing nations in talks with the world’s richest states.

The latest sign of this was US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s decision to skip Thursday’s meeting of G20 finance ministers in South Africa, preferring to send a lower-ranking official instead.

Bessent skipped a similar meeting in February, while Secretary of State Marco Rubio stayed away from a meeting of G20 foreign ministers, saying Ramaphosa’s government was doing “very bad things” and he could not “coddle anti-Americanism”.

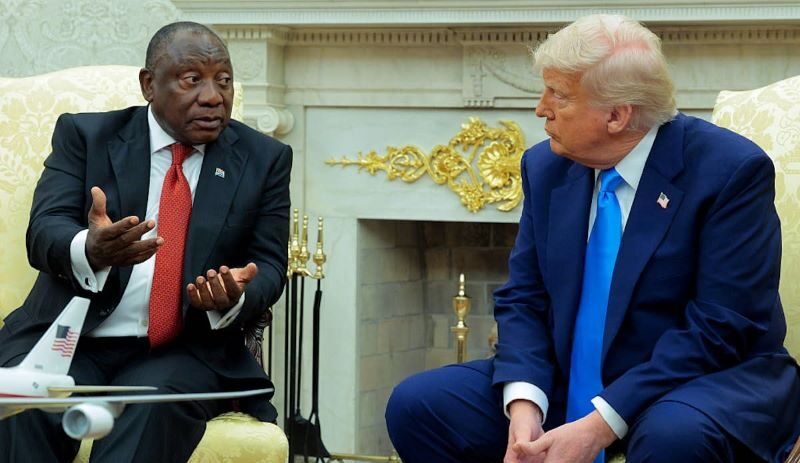

Ramaphosa had hoped to get relations with the US back on an even keel after Trump invited him to the Oval Office in May – only for the US president to ambush him by showing footage and brandishing a sheaf of spurious reports to advance his widely discredited claim that a genocide was taking place against white people in South Africa.

Jonas was strikingly absent from Ramaphosa’s high-powered delegation, giving credence to the DA’s claim that he was unwelcome in Washington.

This put South Africa back to square one as the US had expelled its ambassador to Washington, Ebrahim Rasool, after he accused Trump, in a leaked speech given at a meeting of a think-tank, of “mobilising a supremacism” and trying to “project white victimhood as a dog whistle” as the white population faced becoming a minority in the US.

In a politically odd decision, Ramaphosa left the post vacant, despite its significance, suggesting that his government had a dearth of well qualified career diplomats who could rebuild relations with South Africa’s second-biggest trading partner.