FOR years, the Maryam Sanda case has sat at the uneasy intersection of crime, power, mercy and justice in Nigeria’s legal imagination. On Friday, that long-running national conversation took a dramatic turn once again, as the Supreme Court delivered what may now stand as the final word in one of the country’s most closely watched homicide cases.

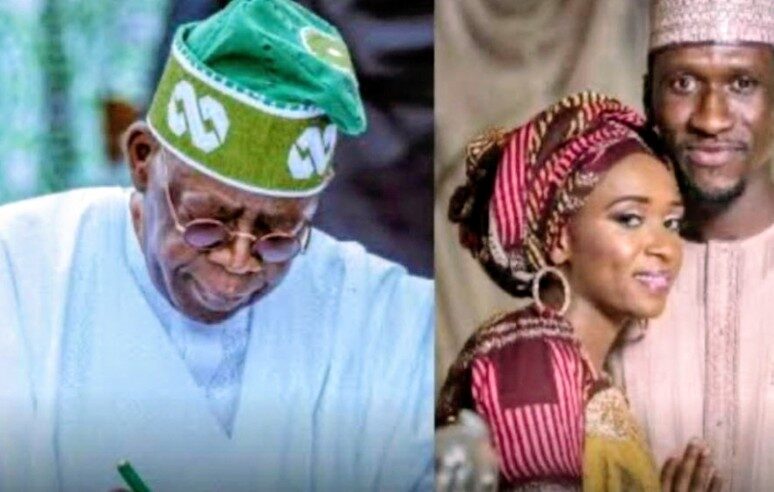

News Point Nigeria reports that the apex court has upheld the death sentence imposed on Maryam Sanda for the killing of her husband, Bilyaminu Bello, bringing fresh intensity to an already polarising case this time in direct contrast to President Bola Tinubu’s earlier decision to commute her punishment on compassionate grounds.

The judgment, delivered by a five-member panel of the Supreme Court in a split decision, reaffirmed the verdict of the trial court and the Court of Appeal, both of which found Sanda guilty of culpable homicide in the 2017 killing that occurred at the couple’s Maitama residence in Abuja.

The ruling effectively nullified the presidential intervention that had reduced her sentence to a 12-year term of imprisonment just weeks earlier.

Maryam Sanda was convicted in January 2020 after a trial that gripped public attention not only because of the violent domestic dispute at its centre, but also because of the social and political weight surrounding the families involved.

Her husband, Bilyaminu Bello, was the son of a former chairman of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), and the case unfolded in the full glare of national scrutiny.

Since her conviction, Sanda has spent nearly seven years in custody at the Suleja Correctional Centre, where, according to prison and government assessments, she maintained good conduct and emerged as what officials later described as a “model inmate.”

Those factors formed the backbone of President Tinubu’s decision earlier this year to grant her clemency. The commutation, announced through an official gazette released by the President’s Special Adviser on Information and Strategy, Bayo Onanuga, cited compassionate grounds, concern for her children, and evidence of rehabilitation.

For a brief moment, it appeared the case had entered a new chapter, one shaped by mercy rather than finality.

That moment, however, proved fleeting.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court dismissed Sanda’s appeal in its entirety, holding that the prosecution had proved its case beyond reasonable doubt. Delivering the lead judgment, Justice Moore Adumein stated that both the trial court and the Court of Appeal had properly evaluated the evidence before arriving at their conclusions.

“The decision of the Court of Appeal, which affirmed the sentence of the trial court, is unassailable,” the court ruled.

More significantly, the apex court took the unusual step of directly faulting the President’s intervention. According to the justices, the executive arm lacks the constitutional authority to issue a pardon or commute a sentence in a matter that is still pending before the courts. To do so, the court held, would amount to an intrusion into the judicial process.

In one stroke, the Supreme Court restored the original sentence and reignited a profound constitutional debate: where does mercy end, and where must the law stand unyielding?

Legal practitioners who spoke to News Point Nigeria were sharply divided, beginning with Barrister Yusuf AbdulSalam, a senior lawyer based in Kano.

According to AbdulSalam, the controversy could have been avoided entirely if proper legal advice had prevailed.

“The President was not properly advised by the Attorney General of the Federation,” he said. “A pardon should come after judgment, not while a case is still in court. If the Supreme Court had acquitted her, the presidential pardon would have been rendered meaningless.”

He questioned the urgency that accompanied the commutation.

“Why give a pardon on a case that has no final judgment? What was the rush?” AbdulSalam asked. “Alternatively, the President could have directed the Attorney General to enter a nolle prosequi and withdraw prosecution entirely. That would have followed a clearer legal path.”

For Barrister Ronke F. Ajiboye, however, the Supreme Court’s position, while legally assertive, raises troubling moral and constitutional questions.

She argued that Section 175 of the Nigerian Constitution clearly empowers the President to grant pardons and commute sentences after conviction, describing clemency as a humanitarian safeguard designed to soften the rigidity of judicial outcomes.

“The authority is neither symbolic nor subordinate,” she said. “It is complementary to judicial power.”

Ajiboye expressed concern that by discountenancing executive clemency, the court risks narrowing a constitutional tool meant to account for rehabilitation, mercy, public interest and social impact.

She also emphasised the human cost of the ruling.

“Maryam Sanda has spent nearly seven years in custody, reportedly showing remorse and reform,” Ajiboye noted. “The pardon recognised her children, her conduct, and the global movement away from capital punishment. Reinstating the death sentence feels punitive rather than corrective.”

Beyond the individual case, she warned that Nigeria’s continued application of the death penalty places it increasingly at odds with international human rights norms and evolving regional standards.

“Justice is not weakened by mercy,” she concluded. “It is strengthened when the law leaves room for compassion and redemption.”

A contrasting view came from Owerri-based senior lawyer, Barrister Kelechi Lawrence, who described the Supreme Court’s judgment as a necessary defence of constitutional order and judicial independence.

According to Lawrence, the ruling reinforces the separation of powers by making it clear that executive clemency cannot pre-empt or override the courts while a matter remains under active adjudication.

“The President’s power of pardon is exercisable after judicial proceedings have concluded,” he said. “Intervening mid-process risks undermining the courts and setting a dangerous precedent where political discretion intrudes into criminal justice.”

Lawrence also pointed to the substance of the case itself, noting that the courts found the evidence sufficient and the sentence legally sound.

“Justice in capital offences must rest on law and evidence, not sympathy,” he argued.

Allowing executive pardon to neutralise a pending appeal, he added, could create the perception that status or proximity to power dilutes accountability.

“By upholding the sentence, the Supreme Court affirmed equality before the law and preserved public confidence in the justice system.”

As the dust settles, the Maryam Sanda case remains more than a legal dispute. It is a mirror reflecting Nigeria’s unresolved struggle with capital punishment, executive power, judicial finality and the place of mercy in modern justice.

Between the President’s gesture of compassion and the Supreme Court’s insistence on constitutional discipline lies a profound question: should justice only punish, or must it also heal?

For now, the law has spoken firmly, finally, and without concession. Whether history will judge that firmness as justice fulfilled or mercy denied is a debate that, like the case itself, is unlikely to fade soon.